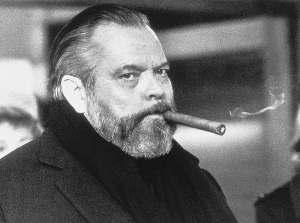

“How much obligation do you feel to a mass audience?” The question comes from a woman in a packed lecture hall, indistinguishable amongst the eager crowd of onlookers. She’s speaking to Orson Welles, and the year is 1981. Welles, now in the latter half of his 60’s, with a full beard and white hair peppered by a few streaks of black, chews over the question for a moment, and looks a tad disgruntled by the thought before replying. “I would love to have a mass audience,” he lobs back, convinced he’s got a winner, “you’re looking at a man who’s been searching for a mass audience...and if I had one I’d be obliged.” He’s right, and the audience laughs along with him before breaking out in applause. It’s a typical late-life Welles witticism, disarming and self-deprecating, while maintaining a cool undercurrent of tired frustration. He was speaking to a group of film students at the University of Southern California after a screening of his 1962 film The Trial, which Welles himself considered the best he ever made. Fittingly, the comment wouldn’t be heard by much of an audience, the clip itself released, not in his planned behind-the-scenes picture, Filming the Trial, but as part of Orson Welles: The One Man Band. The film is a mix of archival and unseen footage about Welles, and was released to little fanfare in 1995. It was assembled by his wife Oja Kodar, as a means of commemorating the tenth anniversary of his death.

More fitting is the content of the film itself: though partly a primer on Welles’ many unfinished projects, One Man Band is more interested in the man than his craft, so far as the two can be separated. It opens with Welles striding onto a stage, and he’s joined by a few stagehands before producing a duck from an empty barrel, as though it were his own special way of saying “hello”. When we return to that university building filled with prospective young filmmakers, the questions focus mainly on personal insights as opposed to industry ones. The film closes with a combination of Welles’ most popular sign-offs, fading into black while reminding you that, “this is Orson Welles, remaining, as always, obediently yours.”

It’s an appropriate goodbye, both for his wife and the viewer at home, as the further we get from Welles' death, the more his presence is missed. While the relative merits of the Welles canon will be the subject of fierce debate for generations to come, the public’s impression of Welles continues to evolve in the aftermath of his passing. Ask one person and you’ll hear about the child prodigy who conquered every medium he applied himself to, only to be sabotaged by studio jealousy and backstabbing. Ask another, and the image of a controlling, gluttonous fraud will be almost impossible to erase from your mind, given the number of such accounts.

He’s an inescapably contrarian figure, all the more so thanks to how little he disguised his ability to be the villain, something friend Peter Bogdanovich knew when telling Welles “no one ever wants to play [Brutus] – but you[1].” It’s a challenge to try and understand a man who “was not his own record keeper; he preferred the myth and fun of making up stories[2],” to quote David Thomson, one of many biographers who has tried to piece together a stabile truth about Welles through all the hearsay. Thomson is in common company among those who, in the decades after Welles’ death, have attempted to pin down what ought to be our final opinion of the man. But only a persona as incendiary as Welles' could make that task such an ongoing affair.

By the time of his twilight years, it seemed the cultural consensus of Welles had already been reached. His increasingly erratic production schedule as director saw only five films completed between 1960 and 1985, two of which were documentaries, and one a made-for-TV movie. In between those completed works were a litany of unfinished passion projects, including a Don Quixote adaptation started with decade’s old footage, and the semi-autobiographical The Other Side of the Wind, which filmed in fits and starts. Supporting these myriad ventures meant assembling funds by any means necessary; Welles had been all but blacklisted among studios over the course of his early years in Hollywood, and his less than triumphant return to American cinema with 1958’s Touch of Evil established his status as box office poison.

Sometimes cashing a cheque meant borrowing hundreds of thousands of dollars from industry pals, of which repayment was often uncertain, or making guest appearances in films of varying note. Other, more infamous ventures involved getting into bed with any and every product that wanted to profit off of Welles’ distinctive voice and domineering figure. Though these were simple jobs meant to pay the bills, his inability to finish any actual projects made these the appearances of “a famous public figure, an inescapable monument for himself,[3]” to quote Thomson; where once was an artist, now sat a washed-up movie star, cashing in as a grocery aisle pitchman. Findus frozen peas and Paul Masson wine remain two of his more memorable patrons, mostly thanks to widely disseminated footage of Welles squabbling backstage with the director, or drunken bloopers, the scandals over which largely eclipsed the ads themselves. All this, combined with Welles’ comic girth, made his winter years the subject of frequent lampooning.

Of all the imitators, John Candy's impression of Welles on SCTV bares the most striking physical resemblance to the Welles of that period, seen practicing a holiday tribute ad with Liberace, only to flub his lines and berate the staff before making off with a turkey. He’d revive the character for the short-lived Billy Crystal Comedy Hour, this time playing on Welles’ penchant for magic by giving Crystal ridiculous requests in an effort to divine a number, only to lose interest -before the trick's payoff-, at the promise of food backstage. The latter bit was filmed in 1982, suggesting that Welles’ appetite, love of magic, and prima donna working antics were his most publicly identifiable traits. A decade after his death, the roasting continued largely unabated, but now in a medium that harkened back to his days as a New York theatre savant. Newspaper caricatures were among the earliest means of bringing Welles to an audience that didn’t frequent Broadway, and his post-mortem media revival would start with a pair of cartoons.

When trying to find the proper cadence for a rat with an oversized head and plans for world domination, voice actor Maurice LaMarche instantly thought of Welles, and the megalomaniacal lab rat called The Brain was born, bringing Orson’s signature voice to a new, much younger generation in The Animaniacs. Adult viewers would also see an animated recreation of Welles on The Critic, a primetime cartoon based on parodies of famous films and actors. Welles’ potential as comic fodder was still fertile territory, with appearances taking shots at his advertising gigs (“I don’t need to do this, I’ve got a fish stick commercial in an hour!”), as well as his size and love for tricks (“I will make this jug of wine disappear”). He'd fair no better outside the world of cartoons. When reproduced in a more mythic fashion for a cameo in 1994’s Ed Wood, the aura of greatness implied by his appearance is tainted by the fact that it’s the world’s most notoriously awful director who looks upon him with such reverence. Bringing back Welles, whether in animated form or in the flesh, was just the setup for a punch line.

Littered throughout all the call-backs to Welles’ troubled final years (Pinky and the Brain recreated Welles’ ignominious rant over a frozen pea commercial nearly verbatim) were references to his actual work, particularly, Citizen Kane. The low-angle podium shot has been replicated ad nauseum, and any close-up of a mouth uttering two syllables is almost assuredly a nod to Rosebud. Much of the awareness of Welles in the years after his death came from parody of Kane, often affectionate (The Simpsons has all but remade the film via references), in one way or another (there was, in fact, a pornographic parody, Citizen Shane, made in 1996). The public may have remembered the man behind The Greatest American Film of All Time as a sell-out and a drunkard, but at least his tarnished reputation had done little to upset Kane’s destined longevity.

What better way then, to re-stoke the gossip and controversy of Welles, than by attacking the golden production which made him a legend, one founded on ambition, ego and a media battle the likes of which only old Hollywood could have pulled off. 1996 saw the drama behind America’s greatest drama revived in The Battle Over Citizen Kane, a PBS documentary that pit the young Welles in a fight to the finish with newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst over the fate of the film. There’s an inherent romanticism to the Kane’s production, described by Paul Arthur in a 2000 edition of Cineaste, where Welles and Kane are “positioned not as distant patriarchal icons of a vanished system but as representative of vibrant artistic struggles against crusty conventions of style and narration.[4]”

That story is largely ignored in the film, which deals more with the reclusive media magnate Hearst, whose use as inspiration for Kane has been well-documented. The documentary goes further to imply that the fighting between Welles and Hearst was merely a passing of the baton, from one generation’s great success-turned-failure to another. Welles is made out to be a brash upstart who made a name for himself fighting Goliath, only to fade into obscurity on the heels of victory. His subsequent works are largely glossed over in the wake of Kane, and the film aims to make tragedy out of an imagined status as a one-hit wonder.

The story would get a dramatization a few years later in RKO 281 (1999), an HBO TV movie that casts similar aspersions on Welles the way the documentary did, but in a grandiose fashion he surely would have admired. The backdoor chicanery of Hearst (James Cromwell) and the conspiratorial meetings of studio heads looking to sabotage Kane have all the cloak and dagger manoeuvring Welles believed had haunted him through his career, while his abuse of scripter Herman “Mank” Mankiewicz (John Malkovich) is portrayed as a betrayal of his own. The same goes for RKO studio head George Schaefer (Roy Scheider), who gets drawn into protecting Kane because of his admiration for Orson, only to lose his job in the process of saving the film. Besides showing Welles' abandonment of those responsible for his initial success, the film, like The Battle Over Citizen Kane, finds other ways to draw strong parallels between Welles and Hearst in “a parable focused on outsized, ill-matched power addicts.” It’s no more apparent than in an invented warning from Hearst to Welles, telling him that “my battle with the world is almost over. Yours, I’m afraid, has just begun.”

It’s insertions like these that, while not quite revisionist, started a trend in Welles fiction, wherein the filmmakers would try and explain the methodology behind Welles’ process, or even try their hand at psychologically probing a ghost. RKO 281 points directly at Mrs. Welles as inspiring the man’s indomitable drive, telling a young Orson, “you were made for the light,” and that “one chance” is all we get in life. It also marks the start of elaborate reference dropping to other works in the Welles canon, in a bid to acknowledge his works beyond Kane, if only in passing. The deathbed-ridden Mrs. Welles looks both like Kane and Mrs. Amberson at the end of their lives, though the tone of her words when giving parting advice to a young Orson gives the impression their relationship had more in common with the Bates family than the Ambersons.

The references themselves were often more complex or subtle than simply reproducing Kane’s most memorable shots. Sometimes the call-outs were used as a means of giving imaginary origins to other Welles works, with throw-away phrases and images made to give the impression that inspiration followed the man wherever he went. Other examples are completely superfluous, like recreating the iconic stairway shot from The Magnificent Ambersons using Hearst and Marion Davies, despite Welles’ not being in the scene. They’re showy and add little beyond letting the filmmaker give a sly wink to the audience that recognizes the homage, but that they exist in the first place hints at appreciation for Welles that extends beyond just Kane.

Less than a month later, Welles was once again in actual theatres for Tim Robbins’ Cradle Will Rock, though this time he was anything but the star. Rather, Welles’ struggle to make Marc Blitzstein’s pro-union musical under the Federal Theatre Project is only one piece of a period labour drama featuring a cast of dozens. It features a young Welles (Angus Macfayden), already a theatre company director at 22, and it’s the most light-hearted portrayal of the man that doesn’t resort to outright mockery. Welles’ famously bitter relationship with John Houseman is used as the basis for good-natured sparring, as their clashes over art and pragmatism provide plenty of comic relief.

Welles is shown as more of a combative artist than a control freak, suggesting that his early days in the theatre lacked the extreme authority issues he was later known for. Likely this was due to the film’s altogether rosy look back at a time of immense political turmoil, but it does posit there was a time when Welles needn’t be the centre of attention to be a part of something great. Maybe he enjoyed being a part of the company’s triumphant first performance despite fear of being cut-off from the theatre community and government funding. Or perhaps, as Thomson believes, Welles was “as romantic and as moved by the demonstration of defiance” as everyone else, but this was just his first taste of the “rush of joy and applause that is only provoked by outrage.[5]”

Focussing on ads, the theatre, and Hollywood leaves the majority of Welles’ actual life and work in the cinema untouched; 281 and Battle lead us to believe that he peaked at 25, glossing over the decades-long struggle Welles faced working in Europe. It’s when his story leaves the glamour of Hollywood and the energy of the New York theatre scene that the real weight of being the industry’s persona non grata comes out, something captured by Vincent D’Onofrio in his 2005 short film, Five Minutes Mr. Welles. Expanding on the interpretation seen briefly in Ed Wood, D’Onofrio’s Welles is in the throes of a professional nadir, trying (and failing) to remember lines for his role as Harry Lime in Carol Reed’s The Third Man. It’s the most unflattering portrayal of Welles out there, keeping him confined to his room, like K in The Trial, in order to heighten the sense of dread and paranoia.

Welles is convinced he’s being watched and spied on, which is actually proven true when assistant Katharine (Janine Theriault) admits she’s been keeping tabs on him for studio higher-ups. Despite showing him as a drinker, womanizer and a clumsy line-reader, there is sympathy to this version, as we get to see how quickly nerves can fray when the world wants you to see you shine almost as badly as it wants to see you explode. Less than ten years after Kane, who wouldn’t believe Welles’ success had more to do with chance than genius? The film settles somewhere in between, as it climaxes in Welles coming up with might be his greatest piece of writing, the cuckoo clock speech. Some would call it the definitive Orson Welles moment, where little details accrued from living over-dramatically at all times synthesize at the last minute out of sheer desperation and a little dumb luck. It would seem that Welles the genius and Welles the fraud were no longer mutually exclusive identities.

2009 brought what could be considered the most layered interpretation of the developing Welles discourse, in Richard Linklater’s Me and Orson Welles, a fictionalized account of the days leading up to the Mercury Theatre Company’s first performance, Caesar. Christian McKay, though looking far too old for a 21 year-old, does better than any of his contemporaries at showing the wild energy and fierce loyalty the young Welles could inspire in people, as well as the fear that came with ever crossing him. He’s a destructive whirligig of ideas and demands, brazen in his manipulation and bullying, particularity evidenced in his often hostile relationship with John Houseman (Eddie Marsan). It’s from a time when he could still get away with virtuoso acts like rewriting a radio play mid-broadcast, as his star was still rising. This was Welles in his prime, a man “driven by a relentless demon,” one that must have been personal and all his own, as Warren Kliewer noted that “his vision of the director as seminal artist and of direction as an art form of its own terms has inspired countless imitations...most lacking Welles’s genius.[6]”

Linklater himself admits the film is far from a biography, and that, as he told the New York Times, “you can see whatever you want there. You can see all the genius, or you can see future tragedy.[7]” Both are present, even in the same moment, no more so than as Welles watches the curtain rise on Caesar’s premiere, noting that “this is the night that either makes me, or fordoes me.” It’s an ironic proclamation, as launching into the artistic stratosphere off of Caesar is what inevitably dooms him; the maverick techniques and furious passion that wows his theatre audience is the same kind that would make him an exile for most his career. Linklater’s Welles is an electric, unstoppable force, unburdened by studio meddling or professional vendettas, and watching McKay is almost like seeing the legendary wonder-boy reborn for a new millennia. We see in Me and Orson Welles the return to his heyday, when it looked like anything and everything was within his reach.

So why then, did it take so long after his death for the world to look back at Welles as anything other than a has-been or a charlatan? Perhaps a new generation, one that could take the long view on Welles’ life instead of just its fading years, would be better able to appreciate what he did accomplish instead of what he didn’t. The proliferation of his work through increased media availability almost certainly aided in bringing more than just Citizen Kane to developing Wellsians, and it didn’t hurt that much of the old guard that harboured some opinion of the man passed along with him in the years since 1985. With the book finally closed on his life, the questions of “what’s next,” and “what horrible thing has he done now,” no longer exist, and the expectations are finally gone.

We can finally view the life of Orson Welles as a whole, and the greatest take away, I believe, is that his was a voice, a passion and a zest for life that is sorely missed. Maybe poking fun of him in cartoons and portraying him as a talentless monster was the best way to reconcile the years after his death with the final years that almost undid his legacy. But the longer the world goes without Orson Welles in it, the more his absence is mourned. It doesn’t matter whether you thought he was a genius, a thief, a bon vivant or a boor, because if he was any or all of these things, at least that brilliant, irascible madman was, as he liked to say, obediently ours. Perhaps he secretly did have a mass audience all these years, as more and more, it seems like, in his own way, he was always obliged to us.

References

1: Welles, Orson, Peter Bogdanovich, and Jonathan Rosenbaum. This Is Orson Welles. New York: Da Capo, 1998. Print.

2,3,5: Thomson, David. Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles. New York: Vintage, 1997. Print.

4: Arthur, Paul. "Reviving Orson: Or Rosebud, Dead or Alive." Cineaste 25.3 (2000). Print.

6: Wilmeth, Don B., and C. W. E. Bigsby. The Cambridge History of American Theatre.Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1999. Print.

7: Lim, Dennis. "Citizen Welles as Myth in the Making." The New York Times. 20 Nov. 2009. Web. 24 Apr. 2012. <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/22/movies/22welles.html?_r=1>.